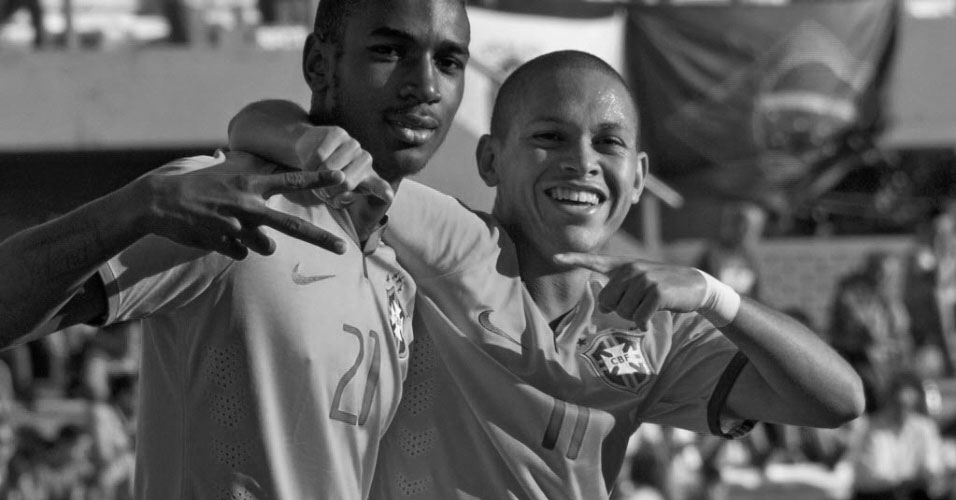

Gerson (left) and Marcos Guilherme were amongst the stand-out players in a poor tournament for Brazil u20s.

Brazil’s first competitive games after the World Cup shambles came in the South American Under-20 Championships, which have just come to a conclusion in Uruguay.

With a young, articulate coach in Alexandre Gallo, who had time to prepare for the competition, this was an excellent opportunity to put last year’s disappointments in the past and show that Brazilian football has licked its wounds, learned its lessons and moved on. That opportunity was emphatically not taken.

True, Brazil did claim one of South America’s four places in the World Under-20 Cup, to be held this June in New Zealand – a considerable improvement on two years ago, when they failed to qualify. But there is not much else to celebrate, and plenty to be miserable about.

Of course, this team had some virtues. There was plenty of physical strength on show, and sparks of individual talent. Midfielder Gerson, just 17, is a huge promise, though it is very early to get excited – he has yet to make his senior debut for Fluminense. His club-mate Kenedy, a couple of years more experienced, is a striker with a howitzer left foot that brings back memories of a young Adriano. Marcos Guilherme is an attacking midfielder with the decidedly useful gift of being able to burst into the penalty area to poach goals, and keeper Marcos had a very sound tournament. And there are few sides who pose as big a threat as Brazil when the opponents have a corner – especially if those opponents are not the strongest. With extreme pace and one pass they can break up the other end and get in a shot on goal.

The problems come, though, when they are denied the space to use that speed, and they have to use more than one pass. Then they looked appallingly, desperately, heartbreakingly limited.

It is, I fear, the same old same old. The virtues described above have been those of Brazilian football in recent years. The defects also. And over the course of a tournament as drawn out as the South American Under-20 Championships, those defects were placed horribly in evidence.

Brazil finished fourth, behind Argentina, Colombia and Uruguay. They could kill rabbits – physically overpowering Peru to score five goals inside 35 second half minutes. But they made not the slightest impression on the stronger teams. It was not only that they failed to score against the sides who finished above them – it is that they failed to ever look like scoring, to give rise to the faintest hope that they might find the guile and imagination to play their way through the opposing defence. Game after game, even in those they won, Gallo’s team looked incapable of stringing together three passes.

There is an old saying in South American football that in the build up zone, the player should forget the goal and look for a team-mate – and if the side keep doing it, sooner or later the goal will appear; the defence will have been pulled around and space will have opened up. This is no longer Brazil’s way. In possession it now seems that they can think about nothing else but the goal – and it is exactly for this reason that they are not getting there. There is no surprise. It is a case of heads down, mindless isolated forward charges. Stick four lamp posts out there instead of an opposing defence and Brazil would run straight into them.

Last year I was involved in making a documentary on Brazil’s 1982 side, which brought with it the happy duties of talking to the players and watching all the games again. The flow of the ball is hypnotic. And there is no dribbling in midfield, no elaborate stepovers on the half way line. Player after player stressed that coach Tele Santana was opposed to such things. The tricks were strictly for undressing the defence in the final 30 metres. In the rest of the field the ball was to be moved, a quick triangle here, a switch of play there. How can this basic grammar of football have been forgotten – especially by the country who dominated it better than anyone? How can Brazilian football, its fans and pundits, have been hoodwinked into believing that creativity is solely an individual asset, when so much of the history of the game is about passing and moving to set up two against one situations?

The football world has moved on in recent years, spurred forward by the extraordinary achievements of Pep Guardiola’s Barcelona. Former Argentina coach Cesar Luis Menotti, one of the game’s finest minds, recently paid tribute to the Guardiola effect:

“It was a devastating hurricane,” he said, “that swept away all the lies and the trickery, in such a way that now even the Italians want to have the ball and play. This hurricane turned into an encouraging breeze in lots of other countries.”

There is, though, an exception – and here an important point must be made. Menotti played for the great Santos side of the 1960s, he loves the tradition of Brazilian football and is rare among his countrymen in believing that Pele was greater than Maradona. His thoughts are not the product of any silly nationalist rivalry, but of a deep love for the game. That encouraging breeze, he continues, has been blowing “everywhere apart from Brazil, where they play worse every day. Today Argentina play better than Brazil, Uruguay play better than Brazil, Chile play much better than Brazil, and so do Colombia.”

And that was before the 2015 South American Under-20 Championships made the point all too clearly.

Final stage table (Wikipedia)